A new AI model can identify diseases faster and more accurately

Multimedia

- 18-11-2024, 21:02

INA - SOURCES

The AI deep learning model enables analysis that could take a year or more to get done within a couple of weeks.

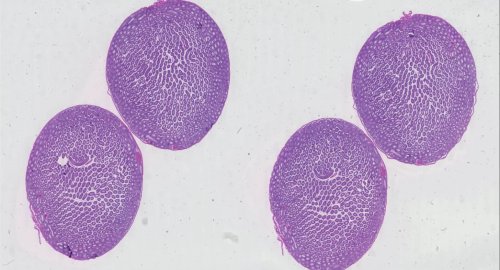

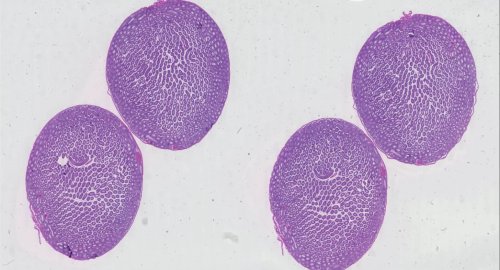

A group of engineers and biologists at Washington State University have developed an artificial intelligence system capable of recognizing signs of disease from images of human tissues. This system uses scalable deep learning to identify infections, exceeding human capabilities in both time and accuracy.

To accurately perform histopathology diagnostics, researchers must integrate AI, computer vision, and medicine. This intersection is the core problem hindering the development of automatic disease detection models.

Additionally, the large size of microscopic images and complex structures at the tissue level adds another layer of tribulation. Finding pathological instances in gigapixel images is an exhaustive task even for humans, which also doubt the real-time applications of any detection model.

A new study published in ScientificReports proposes a new deep learning model that efficiently identifies errors in gigapixel histopathology slides. This novel approach could increase the pace of disease-related research, which requires hours for pathologists to identify instances.

This AI model uses two components: data preparation and the deep learning model. In data preparation, a sliding window is used to view multiple resolutions of subsections of an image. For this, researchers used images from past epigenetic studies conducted by Skinner’s laboratory.

These images contained signs of disease in the kidney, testes, and ovarian tissues of rats and mice. To add extra input to the AI, researchers fed it with more gigapixel images, including breast cancer and lymph node metastasis.

During the testing, researchers found that the new AI model was more efficient and accurate than the previous systems. Interestingly, it even identified pathologies that were missed by trained humans.

Al-Maliki: Iraq Managed the Electoral Process Smoothly

- politics

- 05:18

Al-Sistani: Tomorrow, the 29th of Ramadan

- Local

- 25/03/29

Al-Amiri warns of any war between Iran and the US

- politics

- 25/04/01