3,200-Year-Old Mesopotamian Perfume Recreated from Ancient Text

- 28-07-2022, 09:20

INA- sources

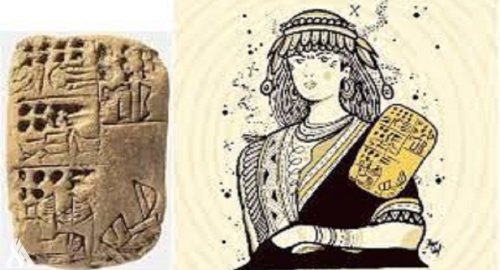

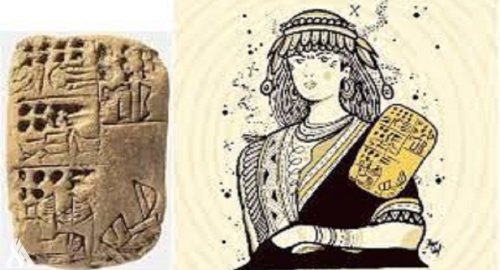

A woman named Tapputi carried the distinction of being the first female chemist in Mesopotamia and the first female perfume maker anywhere in the world, approximately 3,200 years ago. Working with a Mesopotamian perfume formula left on an ancient clay tablet that Tapputi herself made, a team of 15 scientists has now successfully recreated one of her Mesopotamian scents in a laboratory setting.

Turkish scientists working in cooperation with Turkey’s Smell Academy and Scent Culture Association (Koku Akademisi ve Koku Kültürü Derneği) carried out an extensive investigation of Tapputi’s Mesopotamian perfume-making methodologies. Their aim was to first understand what she did, and then possibly duplicate her work in as much detail as possible. They have now partially achieved their goals, although the efforts to translate and interpret the legendary Tapputi’s work will continue.

tapputi’s Mesopotamian Perfumes Etched in Ancient Clay

Archaeologists found Tapputi’s name inscribed on a pair of cuneiform tablets recovered during excavations in southern Turkey, which was part of Babylonian Mesopotamia in the second millennium BC. The tablets gave her full name as Tapputi-Belatekallim, with Belatekallim meaning “a female overseer of a palace.” The tablets were dated to 1200 BC, and in their inscriptions Tapputi was described as a registered chemist and expert producer of fine Mesopotamian perfumes (which are unprecedented titles for a woman who lived that far in the past!).

On the tablets, Tapputi recorded her Mesopotamian perfume formulas and the steps she used to produce her scents in ancient Akkadian. Fortunately, scholars know enough about this language that it was possible to translate what she had written.

To make her ancient perfumes, the recovered tablets revealed Tapputi used a combination of different types of flowers, oil, calamus, Cyperus, myrrh, horseradish, spices, and balsam, to name just a few of the ingredients identified. She would mix her various concoctions with water or other solvents, distill them, and then filter her liquid product many times to create a purer and more pleasant-smelling Mesopotamian perfume formula.

Out of this complex jumble of Mesopotamian information, they were able to eventually recreate one of her scent formulas in its entirety.

As a part of her methodology, Ergül reveals, Tapputi would work under a full moon while seeking communion with the stars in the night sky. This esoteric aspect to her Mesopotamian perfume-making activities was one of many secrets uncovered during translations of the two tablets that discussed Tapputi’s innovative modus operandi.

Ergül and her team of experts produced 27 pages of translation from the two tablets, which were recovered during excavations near Harran, a sleepy village in Turkey that was a major urban center during Mesopotamian times.

“As the Fragrance Culture Association, we are keeping alive the scent traditions that have existed on these lands,” Ergül stated. We live on a land that has an 8,000-year-old scent culture.” The fragrance expert noted that there were hundreds of tablets that touch on fragrance production in ancient Mesopotamia unearthed during the excavations, and much work remains to translate them all.

Uncovering the Brilliance of the World’s First Known Female Perfume Maker

In addition to Ergül, there were 15 experts involved in this new study of Tapputi and her innovative work. These included Professor Mehmet Önal, an archaeologist from Ozyegin University who led the excavations at Harran, and Associate Professor Cenker Atila, an archaeologist from Sivas Cumhuriyet University and an expert on ancient ceramics, glass works, and perfumes. The research was carried out on artifacts that were previously recovered and have only now been translated after three years of strenuous and dedicated effort.

While they discovered enough to identify all the ingredients used in one of Tapputi’s scents, proceeding beyond this point could be a challenge. Atila highlights two problems his team has faced as they’ve attempted to learn more about Tapputi and her work.

Moving beyond the decoding of formulas and methodologies to the actual recreation of scents in a lab represents a big step. It has been done once so far, and the researchers hope they will be able to resurrect even more scents in the years to come, which will provide direct evidence of Tapputi’s true brilliance as the world’s first recorded female perfume-maker.

Al-Maliki: Iraq Managed the Electoral Process Smoothly

- politics

- 05:18

Al-Sistani: Tomorrow, the 29th of Ramadan

- Local

- 25/03/29

Al-Amiri warns of any war between Iran and the US

- politics

- 25/04/01