Gene-edited pig kidney keeps monkey alive for 2 years, trial finds, a step toward longer-lasting human transplants

- 15-10-2023, 09:31

INA- sources

About 13 people die every day while waiting for a kidney transplant because of a lack of organ donors, but some scientists think pigs could be the answer. In a new trial that researchers say is the largest of its kind, researchers transplanted kidneys from genetically modified pigs into monkeys that lived for what’s considered a record amount of time.

These scientists hope their proof-of-concept study, published in the journal Nature this week, could soon lead to human trials.

In the United States, more than 90,000 people are on a waiting list for a new kidney because one or both of theirs have failed. Globally, about 8% to 16% of people have kidney problems, and it is a leading cause of death, killing more than 250,000 people in 2019, studies show. Dialysis can help remove waste and extra fluids in the blood, but it does only 10% to 15% of the work of a healthy kidney, and people on dialysis face a 50% chance of dying within five years of going on the treatment, studies show.

About 170 million people in the US have signed up to be organ donors, but only 3 in 1,000 people die in such a way that their organs would be viable for transplant, according to US government numbers.

Scientists have been looking for alternatives, and several teams of researchers have been experimenting to see whether pig organs may be an option because they are anatomically similar to human organs, and pigs reproduce quickly.

For the new study, scientists picked the Yucatan breed of pig because it has a similar weight to the average American woman: about 150 pounds. Its kidney is also about the same size as a human’s.

The scientists genetically modified the pigs so their kidneys could be transferred to another species and to improve the chances that the organs wouldn’t be rejected. Even when a human donates an organ to another human, the recipient has to take drugs to suppress their immune system for the rest of their lives so their body does not reject the donor organ.

With previous pig-to-primate donation experiments, even those involving genetically modified pigs, scientists had to use a significant number of immunosuppressant drugs, meaning the experiments would not be translatable to a human organ donation experiment, researchers said. But with this trial, the genetic modifications were effective enough that they needed only about as much medicine as a human could tolerate.

Three gene modifications in the pig were critical, the researchers said. One knocked out the part of the genes that make glycol antigens, chain-like structures made up of sugar molecules that could trigger the recipient’s body to reject the kidney. Other teams have used this kind of gene edit, but the recipient animals didn’t live as long.

The researchers behind the new study say that two additional gene edits seemed to be key to extending the monkeys’ lives in this study.

The second edit was to insert seven human genes that regulate kidney rejection pathways. The researchers also inactivated androgynous retroviruses – the remnants of ancient viral infections that are latent or inactive in the pig – to keep them from becoming active once the organ was transplanted into another species.

The full combination of gene edits, combined with the immunosuppressive drugs, seemed to support what researchers considered long-term survival.

The team transplanted pig kidneys into more than 20 monkeys, although not all of the pigs had all of the gene edits.

None of the monkeys that got kidneys from the pigs without the seven human genes survived more than 50 days. The monkeys that got the full combination lived a lot longer: Five lived for more than a year, and one lived for more than two. Tests showed that the single donated kidney seemed to perform as well as two natural kidneys.

“We’re the only group in the field to comprehensively address safety and efficacy of our donor organ with these edits,” said study co-author Dr. Mike Curtis, president and CEO of eGenesis, a company working on innovation in the field of organ transplantation.

Curtis said the study authors will work with the US Food and Drug Administration in the next few months on creating a path to start clinical trials in humans.

Dr. Robert Montgomery, director of the NYU Langone Transplant Institute, believes that the new trial is “an important contribution showing improved survival of extensively gene edited pig kidneys in nonhuman primates.”

Montgomery was not involved with the new study, but in July, he led a team that transplanted a genetically modified pig kidney into a human. The organ functioned for about two months before they removed it at a predetermined date. It was the longest documented case of a xenotransplant – a transplant between two species – of its kind.

Montgomery wrote in an email that the new study is good support for moving to human clinical trials “sooner rather than later.” However, he cautions that there is some theoretical risk, in terms of safety, introducing the “vast array of gene edits” that the authors did on the donor pigs.

“Unintended off target effects of these edits and inconsistent levels of transgene expression between pigs will be difficult to assess and will present a burdensome regulatory challenge,” he wrote.

Montgomery added that the nonhuman primate model continues to be controversial in terms of how well its results will translate to a pig to human transplant.

Other recent pig-to-human transplants have had some success.

In January 2022, researchers at the University of Maryland transplanted a heart from a genetically modified pig into a 57-year-old Maryland man. The man had terminal heart disease, and his medical history made him ineligible to receive a heart from a human donor. Doctors said the transplant went well, but the man died after two months.

In September, a 58-year-old man with end-stage heart disease got a donor heart from a genetically modified pig, and he is still alive.

source: CNN

Court confirms sacking of South Korean president who declared martial law

- International

- 10:25

Trump unveils $5 million ‘gold card’ for rich migrants emblazoned with his image

- International

- 08:59

National Security Agency chief and deputy director dismissed

- International

- 08:49

La Liga continues to pressure Barcelona

- Sport

- 09:47

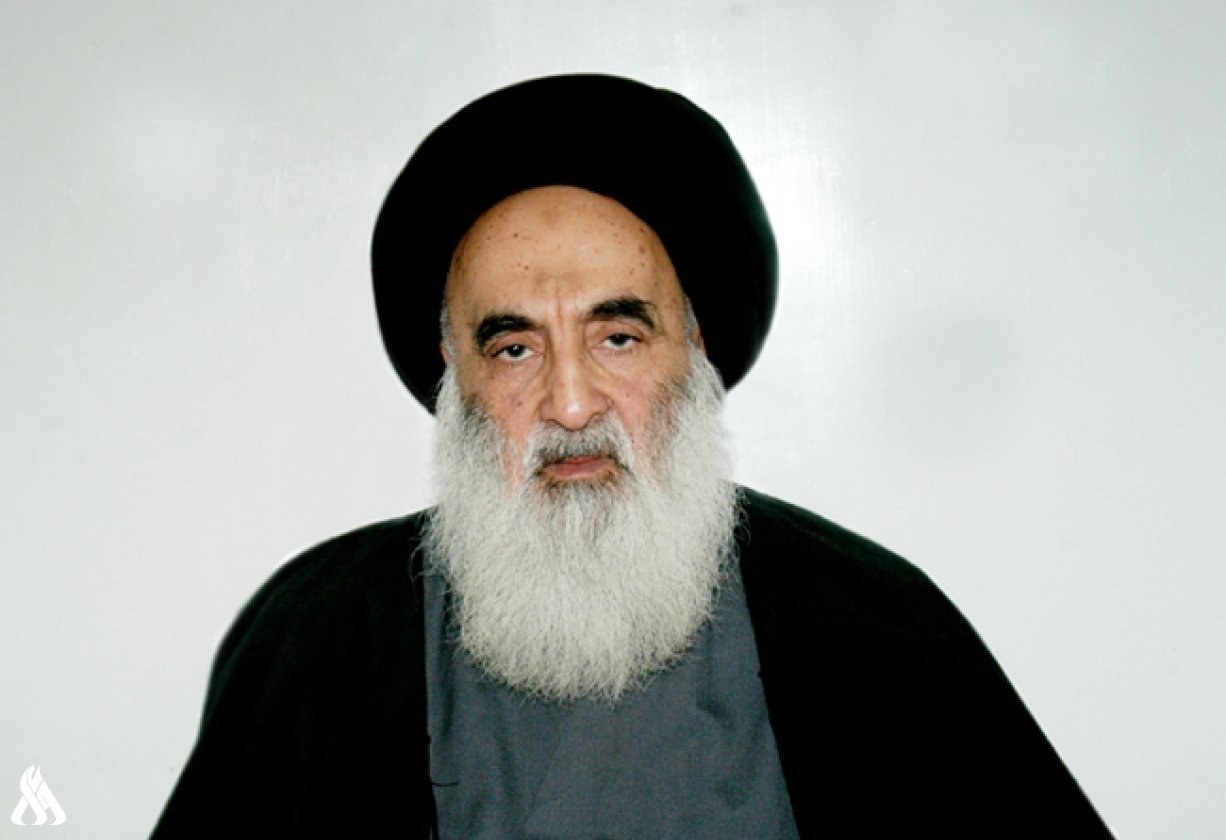

Al-Sistani: Tomorrow, the 29th of Ramadan

- Local

- 25/03/29

Al-Amiri warns of any war between Iran and the US

- politics

- 25/04/01